|

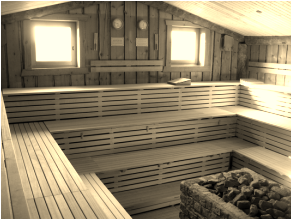

This post was written by Will Ng, 2nd Dan. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect that of the Mayfair branch nor the BSKF.  I was sitting in the sauna the other day, and the heat was becoming excruciating after about 10 minutes. 3 more minutes, I said to myself, but no matter how much I stared at it and willed it on, the minute hand did not budge. So to pass time more quickly, I started reciting the Dokun, which by my reckoning would kill a minute or two. Not out loud of course, otherwise it would have been a little weird for other people in that small oven. If you are reading this and have no idea what the Dokun is - it is basically the creed that we recite every class as part of our philosophy and zen training. It is divided into 3 sections - Seiku, Seigan and Shinjo. Bearing in mind I have trained Shorinji Kempo for almost 12 years, and have said the whole thing from start to finish every single class... I could not get past the first couple of lines. From the 2nd section on, words started to mix and match, sentences were merging, and didn't make sense any more. Meanwhile the clock hand still hasn't moved. Or maybe it did. It was getting really hot in there. And no matter how hard I tried, I couldn't remember all the words of the Dokun from start to finish. All I knew at that very moment was the heat, sweat beads dripping and falling in slow motion, the hot air burning my nostrils and suffocating my lungs. All I could think about was the cool outside. There were two lessons there, I think. First lesson: dealing with pressure When your body is under pressure, it is very difficult to focus on things other than the cause of that pressure, in my case the heat. But translate that to a daily life situation - maybe a job interview, or a client meeting, or if you had to face a violent aggressor - this still holds true. When we are put under pressure, evolution has programmed us to focus on the cause of that pressure. It forces us to deal with it, mitigate the risk, and get back to safety. While most of the 'pressures' we encounter in modern life are no where near as life-threatening as those cavemen days, we have retained this natural instinct. Naturally, if you have to square up to someone who is threatening to punch/kick/stab you, the last thing you want to do is lose focus of them. But they should not be your sole focus. While the aggressor should have your full attention, you also need to be aware of everything else in your surroundings. Two concepts are important here - heijoshin which means 'calm mind', and happo moku which means 'peripheral vision'. Does the aggressor have friends? Is there traffic on the road next to me that I could accidentally step into? Am I backing into a wall? Are there any objects within my reach that I could use to protect myself with? Frustratingly, it was obvious that my mind was not calm nor cool (excuse the pun) enough to not think about the heat and just think about the Dokun. Luckily for me, no one was about to attack me in the sauna. Second lesson: complacency I clearly don't 'know' the Dokun (or whatever one could recite to kill 3 minutes). Of course I know all the words in the right order, but only if there were spoken in a very specific context - in class, together with several other people, preceded and followed by certain actions. It was not second nature. Often we become familiar with something, then take it for granted. We become complacent, and stop thinking about why we are doing it. We stop trying to add variations, or doing it in different contexts. We get stuck in the rut. We just go along with it, and go through the motions. In a way it is second nature, but it's a false second nature. The attacker must attack with their back fist standing no closer than a metre from me and only then can I, if all other preconditions are satisfied, effectively dodge, block and counter the attack. Sadly it doesn't work like that, just like the lessons the Dokun tries to teach cannot simply be applied in real life by reciting it (in such a way that if I want the stuff from the 3rd section I would have to recite the 1st and 2nd sections first before I can remember the 3rd). Incidentally I wondered if my physical training - the techniques, body movements, footwork, etc - would fall foul of the same fallacy. If put under pressure would I still be able to apply the principles of kempo as I do in class? No idea, and I'm not about to field-test it. A good exercise here would be Randori though. So it appears that I still have much to learn and practise. Next time I'm in the sauna perhaps I should try counting sheep instead. Or perhaps I should just not look at the clock, close my eyes, and let the time pass by itself.

0 Comments

This post was written by Will Ng, 2nd Dan. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect that of the Mayfair branch nor the BSKF.  I have the Japanese 一期一会 (ichi-go ichi-e) embroidered onto my belt. Ichi-go ichi-e The phrase can be translated as "living every moment as if it was the last", or "every moment is a unique opportunity". My reading of it is that opportunities are only momentary, that they only come round once. If you miss it, then it's gone forever, so make sure you make the most of everything and live every day as if it was the last. Of all the teachings in Shorinji Kempo, I chose this phrase to be embroidered on my black belt 6 years ago because it resonated with me most. It was something I truly believed it, but I have always felt that I don't practice it as much or as well as I should. I wanted the embroidery to be a constant reminder. The ideas behind the phrase aren't too radical and similar sayings can be found across many different cultures and languages. Nonetheless we don't tend to use them all the time; they sound quite serious (I mean, it is a bit morbid to assume every moment to be one's last!) - though more likely it has become a bit of a cliché. But when I heard the tragic news about the cyclist who was killed by a lorry the other week, I also learned that she was a friend of a friend. It was quite a sobering moment - the realisation that the beauty and miracle of a living human being can be taken away and wiped out in an instant, that it can happen to just about anyone, not just those who are far far away in some distant land, but also those who are very close by, physically and metaphorically. Let's not kid ourselves. In a way a lot of us have become desensitised to the realities of life and death, presumably through the overload of online media and global connectivity. The phrase ichi-go ichi-e isn't just another cliché anymore; it is very real. I went to training that evening and with the news still fairly fresh in my head. It was strange, because after about 5 minutes into kihon my training changed, as if a switch inside of me was flicked. Every punch, every kick, every block, every ki'ai - they all became very purposeful. I could feel my body giving it all, but it wasn't because I was being more aggressive, or running on a sugar high. No, I think the difference came first from the mind which was translated to my body and its movements. It was not aggression, it was purpose. But shouldn't I be training like that every class anyway? Shouldn't every movement be purposeful? If not then why even bother? Why even bother turning up if all one does is to go through the motions? Shorinji Kempo - or anything else for that matter - isn't just about training the body; it is also about training the mind. It is our mental state and our attitudes too. Time is too precious to waste, so why waste it doing something if we don't give it our all and our very best efforts? Training in the dojo isn't just about throwing your arms and legs around and getting a sweat out of it. Sure, some of the basic training (kihon) is done every class and may seem repetitive, but do we always consciously and critically ask ourselves, if that punch or that kick we've just thrown is better than the last one? Do we consciously focus on a specific area we want to improve on (e.g. body motion, footwork, weight distribution, etc) every time we perform an action? How often do we question our motivation for training, or doing something in life? Or are we satisfied with following along, riding the wave with everyone else thoughtlessly? Life is too short, so let's make sure every moment is purposeful and meaningful. Ichi-go ichi-e. I'd like to use this opportunity to offer my most sincere condolences to the friends and family of Ying Tao, the cyclist killed in the tragedy cited above. May she rest in peace. |

Archives

June 2016

Categories

All

|